At 85, Dr. Jane Goodall is as observant as ever. She instantly sees that my tie has little gorillas on it, a souvenir from our trip to see the mountain gorillas in Rwanda. She also observes that I’m writing a story for a veterinary publication. She notes her familiarity with the so–called ‘Gorilla Doctors’ or Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project, who actually treat mountain and Grauer’s gorillas.

“Veterinarians are very important; you know, I so appreciate what they do,” she starts. “Not only for our pets, but now in the wild as well.”

Happily, these days, the non–profit Gorilla Doctors are rarely called in to remove snares, but gorillas do get sick (sometimes as a result of close contact to humans due to ecotourism) or injured. And the ‘gorilla docs’ are notified instantly by guides that take tourists to see the gorillas.

Goodall says that those gorilla tourist dollars, which are re–invested back to protect the great apes, combined with the veterinary care, are responsible for the success of the species. They’re the only great ape increasing in numbers, albeit very slowly. All others are losing numbers and imperiled.

Goodall is a fan of ecotourism, if managed properly. “Unfortunately, it can get out of hand, destroying the very nature people travel so far to see,” she says.

I told Goodall that the hottest thing going on now in veterinary medicine is an initiative called Fear Free, which she hadn’t heard of. When I explained the concept, she said that the idea resonates—considering animal emotions are something she once fought for.

It’s hard to think of Goodall as a controversial figure, but when she first began her observational notes on chimpanzee behavior at Gombe National Park in Tanzania in the early 1960’s, she was criticized by her colleagues for naming her subjects, recording individual personality traits and documenting emotions.

“I was told to give the chimps numbers, not names,” she says. “Scientists then were outraged that I actually recorded and wrote about individual personalities and emotions because, according to them, personalities and emotions were restricted only to humans. As a child, I learned from my dog and other dogs in the neighborhood; they all have their own personalities.” Goodall pauses and laughs, “Of course anyone with pet cats and dogs have known this for a very long time.”

Goodall persevered, adding that, if she knew dogs expressed and felt various emotions—similar to our own—the same must be true for our closest relatives.

Goodall smiles and holds up plush animals she had laid out on the sofa next to her. “This is why I travel with Ratty (a plush rat). Even rats have feelings,” she says, as she holds up Ratty. “And cows (she now holds up a plush cow); it’s horrible how we sometimes treat cows, as if they have no feelings, but they do. And pigs (now holding up her plush pig); they’re as smart as dogs.”

Goodall says that by the time she received her PhD at Cambridge, her work was publicized by National Geographic, and chimps she had named, like David Greybeard, Mr. McGregor and Goliath, were known to TV audiences. At that time, this further outraged the scientific community.

“I was told that I was doing everything wrong,” she says. “Their feeling was that I couldn’t write or talk about animal emotions because they don’t exist.”

Of course, fast forward to today, based on neurochemistry found in their brains, we know animals do feel real emotions. And, all great apes have nearly identical brain chemistry to ours.

Goodall supports the notion of Fear Free. “I do know there are ways of alleviating fear in animals,” she says. “Why wouldn’t we help to fix it?”

Today, Goodall travels non-stop, over 300 days annually across the globe, as an advocate for protecting the planet. And, there’s talk of her earning a Nobel Peace Prize because she’s making the world a better place, for humans and animals—for the entire planet.

In Gombe, the Jane Goodall Institute has afforded people improved healthcare and education, and offered various tools to get out of poverty, all in ways which they suggest.

“So now cutting down the forests is no longer necessary to improve their lives,” she says. “They now understand that saving the forests isn’t only saving chimpanzees and other wildlife, it will also save future generations of their people. So they’ve become partners with the environment. Where there were barren hills around Gombe, now trees have come back.”

This program is a model, which now has been replicated in six other African countries.

She adds that we must carry hope to the next generation. That’s one reason why she launched her Roots and Shoots program for children, starting with 12 students in Tanzania in 1991. Today there are Roots and Shoots programs in 50 nations, and by now, many thousands of young people have completed the program.

“The idea is that whether you live in China or the U.S. or in Africa, we are all the same,” she says. “True, we live in different environments, our cultures may be different and our religions may be different—but we all share two fundamental facts. We are all human. And we all live on the same planet. Each Roots and Shoots program chooses three projects of their own choice; one to help animals, one to help people and another to help the environment. I think we have around 2,000 groups across China alone.”

She continues, “I am confident that young people are rising to the challenge. They must. It’s our future. They realize what’s happening. They can’t ignore climate change, and how forests are disappearing, and how our oceans are filled with plastics. They are our hope for tomorrow.

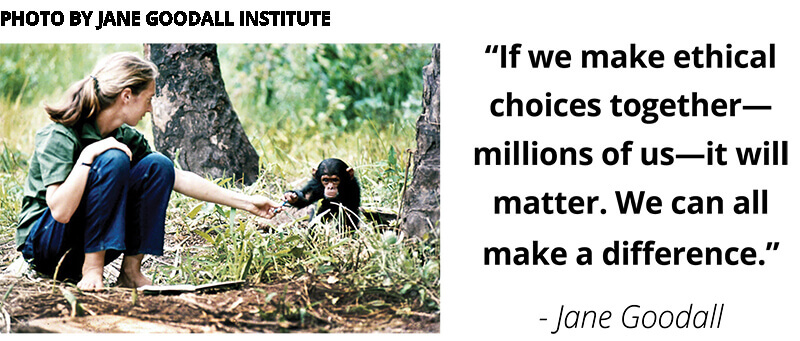

“Every single day, every single one of us lives—every one of us makes an impact on the planet,” she continues. “We have a choice about what that impact will be. And consider even the little choices, like what we buy. Did it harm animals? Will it harm the environment? Is it cheap because of child slave labor? If we make ethical choices together—millions of us—it will matter. We can all make a difference.”

Officially, Jane Goodall is a United Nations Messenger of Peace. She has touched millions of lives, but that’s not enough, as the world clearly remains a dangerous place, and our planet itself is at risk as a result of climate change. She agrees that the Nobel Prize would allow her to reach even millions more.

Still, even Goodall must take a breath every now and then. I asked her what makes her happiest. “The serenity of being out in a forest,” she says. “And spending time with a dog,” she pauses, as I note that we evolved with dogs. “That’s right, and dogs are very special and so are those who care for them.” +